Abstracts or Introductory Material for Articles in Historical Archaeology in Wisconsin

Searching for Evidence of Protohistoric and Early Colonial Encounters in Wisconsin

Heather Walder

This chapter summarizes archaeological evidence for contact-era or “protohistoric” and early colonial period Native American lifeways of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries in Wisconsin. A brief discussion of terminology (including protohistory, early historic, contact, early colonial, etc.) will precede the review of evidence by region. These include eastern Wisconsin and protohistoric Ho-Chunk and Menominee, western Wisconsin’s late precontact sites and the protohistoric Ioway, and northern Wisconsin’s protohistoric potentials in the Northern Highlands and other areas, including possible seventeenth-century Anishinaabeg or other sites around Chequamegon Bay and in northwestern Wisconsin. Archaeological evidence for the historically documented migrations and early colonial-era activities of later arrivals, including the Potawatomi, Meskwaki, and Wendat (Huron) and related groups are also discussed. In sum, the study of protohistoric interactions in Wisconsin has progressed in recent decades, but the archaeological evidence of early exchanges and colonial encounters remains to be uncovered and investigated.

Figure 3. The Markman site (47WP085) has a typical “protohistoric” artifact assemblage including (clockwise from top left): a large piece of metal kettle scrap with one edge folded; an iconographic ring with an L-Heart design; a ceramic body sherd described as Butte des Mort Incised; a blue glass trade bead of type IIa40; and the point of a French iron clasp knife. (Original images by Jeffery Behm, composite by the author.)

The French Fur Trade in Wisconsin, Early 1600s to 1760

Robert A. Birmingham

“The first white man we knew, was a Frenchman—he lived among us, as we did, he painted himself, he smoked his pipe with us, sung and danced with us, and married one of our [women], but he wanted to buy no land from us!”

[From speech by Little Elk (Ho-Chunk) at Prairie du Chien in 1829; as quoted in Atwater 1831].

The name of the first European to see the lands that are now Wisconsin and meet the Native people who lived here is unknown, but certainly it was a Frenchman. In the early 1600s the French sought to expand the lucrative fur trade to the western Great Lakes fromthe fur trade centers and colonies at Quebec and Montreal.Young explorer Étienne Brûlé might have traveled as far as Lake Superior in 1622 (Ross 1960:14). Jean Nicolet came to the western Great Lakes in 1634 with a small group of Huron to meet with the Ho Chunk gara or Ho-Chunk (known to the French as Puan), to facilitatea peace between them and more easterly tribes who were involved in French trade as middlemen (Lurie and Jung 2009). The French fur trade is an important chapter inthe histories of North America, Native Nations, and the state of Wisconsin. The purposes of this paper are to provide a historical background for this enterprise and period, review the historical and archaeological evidence for French fur trade sites in Wisconsin, and suggest recommendations for future research.

Figure 4. French clasp knives: above, photograph of Bell site hawk bill style knives (adapted from Behm 2008:Figure 47); below, drawings of later Marina site sword pointed style (from Birmingham and Salzer 1984:240, Figure 87).

Historical Archaeologies of Indigenous Communities in Wisconsin: Introduction and Historical Context

Addison P. Kimmel and David F. Overstreet

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the land today known as Wisconsin was Indian Country. While its French-speaking residents may still have thought of it as part of the pays d’en haut, or upper country, and a rare anglophone American occupant may have called it by its current colonial name, Indiana Territory, to the Menominees and Ho-Chunks living on these lands—as they have since time immemorial—this was their homeland (Jones et al. 2011:15).

In this series of papers, the authors seek to highlight and document, through historical archaeology, the lives and lifeways, resilience, and enduring presence of the Indigenous people who have lived in this place over the last two hundred years. In their section on Ho-Chunk archaeology, Addison Kimmel and William Quackenbush discuss the work of earlier anthropologists and archaeologists like Bob Hall and Janet Spector at nineteenth-century Ho-Chunk village sites, as well as more recent archaeological work done at late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century sites of return. Overstreet and Grignon discuss the Menominee Tribe during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the ways in which these communities were intimately connected to earlier ones. Cynthia M. Stiles’s contribution explores the material footprints left behind by resilient Ojibwe communities in Wisconsin from the Treaty Era into the late twentieth century. Concluding this section, Robert Sasso’s contribution synthesizes over thirty years of ethnohistorical and archaeological investigations into Potawatomisites and material culture in southeastern Wisconsin. The section concludes with “Future Directions in the Archaeology of Wisconsin’s Native Communities,” by Addison P. Kimmel.

Figure 6. Rice harvesting on Shawano Lake (ca. 1925); (courtesy of the Milwaukee Public Museum, #31325).

Introduction to Wisconsin Military Archaeology

Jonathan Van Beckum

Wisconsin’s complex military history ranges from conflicts between Native communities and European colonizers, to skirmishes between the early American Republic and the British in the War of 1812, to the troubles associated with the removal of Native peoples during the 1800s. This collection of articles represents efforts by historians and archaeologists to uncover that past military history using both archaeological excavation and archival research methods. Here, we share Wisconsin’s military history from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries.

This section begins with an article by Jonathan Van Beckum that summarizes the efforts to utilize archival sources and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) data to better locate and describe the layout of Fort Shelby, a War of 1812 American fortification and battle site in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. In the next article, Vicki Twinde-Javner describes First Fort Crawford (1816–1829) and excavations at Second Fort Crawford (1829–1865). The third article by Kevin Cullen describes public archaeology efforts at Fort Howard in Green Bay, which was an American military installation from 1816 to 1852. The final article, by Robert A. Birmingham, provides a brief history of the Black Hawk War, which occurred in 1832 and was fought across portions of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Illinois. This uprising by the Native inhabitants of this region was in response to treaty disputes and efforts to forcibly remove them from their land, and sparked the construction of numerous small fortifications in the affected area.

Figure 3. Enlisted men’s quarters at Second Fort Crawford exposed in 1999.

Historic Euro-American Farmsteads of Wisconsin

Paul Reckner

This essay focuses on archaeological approaches to Wisconsin’s historic farmsteads. There is no question that Native peoples practiced horticulture and agriculture at various scales prior to the arrival of Europeans in Wisconsin. But with the expansion of European settlement into the region from the mid-seventeenth century onward, farmers and farming quite literally conquered the countryside. The various farming traditions brought to Wisconsin by European immigrants sustained a mushrooming population, structured the regional economy, reworked the landscape, and informed the character of a complex, multi-ethnic immigrant community. Working in an historical archaeological framework, documentary sources are considered to be equal to archaeological evidence in terms of their importance to the holistic interpretation of farmstead sites. Issues of farmstead research potential and significance are considered first, after which an overview of attempts to periodizeand thematize Wisconsin’s agricultural development is presented. The core of the discussion consists of a thematic summary of existing research in Wisconsin.

Figure 6. Profile of bisected, stratified privy vault deposit at the Stephen Field Farmstead (47WL351) site.

Lead and Zinc Mining in the Upper Mississippi Valley and Its Archaeological Potential

Philip G. Millhouse

This essay examines the history, sites, and landscapes of lead and zinc mining in the southern Driftless Area. The area contains rich deposits of lead ore that were mined and traded by Native Americans for many millennia. This activity drew the attention of the competing colonial powers, finally falling into the hands of the expanding United States. Using the reprehensible Treaty of 1804 as justification, the U.S. opened the lands to prospectors against the protest of resident Native American people. The lead rush created predictable clashes with Native American residents, resulting in genocidal warfare, removal of survivors, and dispossession. The following century and a half saw the establishment of the longest continuous duration mining district in United States history. Over this time span mining technologies changed, production shifted to extraction of zinc ore, and regional communities adjusted to an industry that expanded and contracted dramatically with fluctuating demands of the market. The goal of this article is to give a brief background into the ore deposits, mining history, and possibilities for future archaeological work in the Upper Mississippi Valley Mining District.

Figure 15. Huglett’s Furnace north of Galena, Illinois. Note the stacks of melted lead bars on the right side of the picture (William C. Millhouse glass plate print).

Past in the Pines: The Archaeology of Historic Era Logging in Wisconsin

Sean B. Dunham, Charles R. Moffat, and Ryan J. Howell

The logging era in Wisconsin, spanning roughly from 1830 to 1945, formed a unique economic and social episode in Wisconsin history. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century logging produced a heavy environmental footprint that still affects the northern Wisconsin landscape and economy today. Moreover, the period also saw a highly mobile and transient use of the landscape that left some well-defined archaeological site types, such as camps and towns, as well asna variety of ephemeral and hard-to-recognize archaeological deposits and features. This paper reviews the archaeological context of historic logging in Wisconsin, some commonly associated site types and landscape features, and the artifacts diagnostic to logging-related sites.

Figure 8. Double-bitted axe head recovered from a ca. 1900 Minnesota logging camp. (Photograph courtesy of Sean B. Dunham.)

Wisconsin CCC Camps as Archaeological Resources: Historic Context, Resource Definition, and Site Documentation

Mark Bruhy

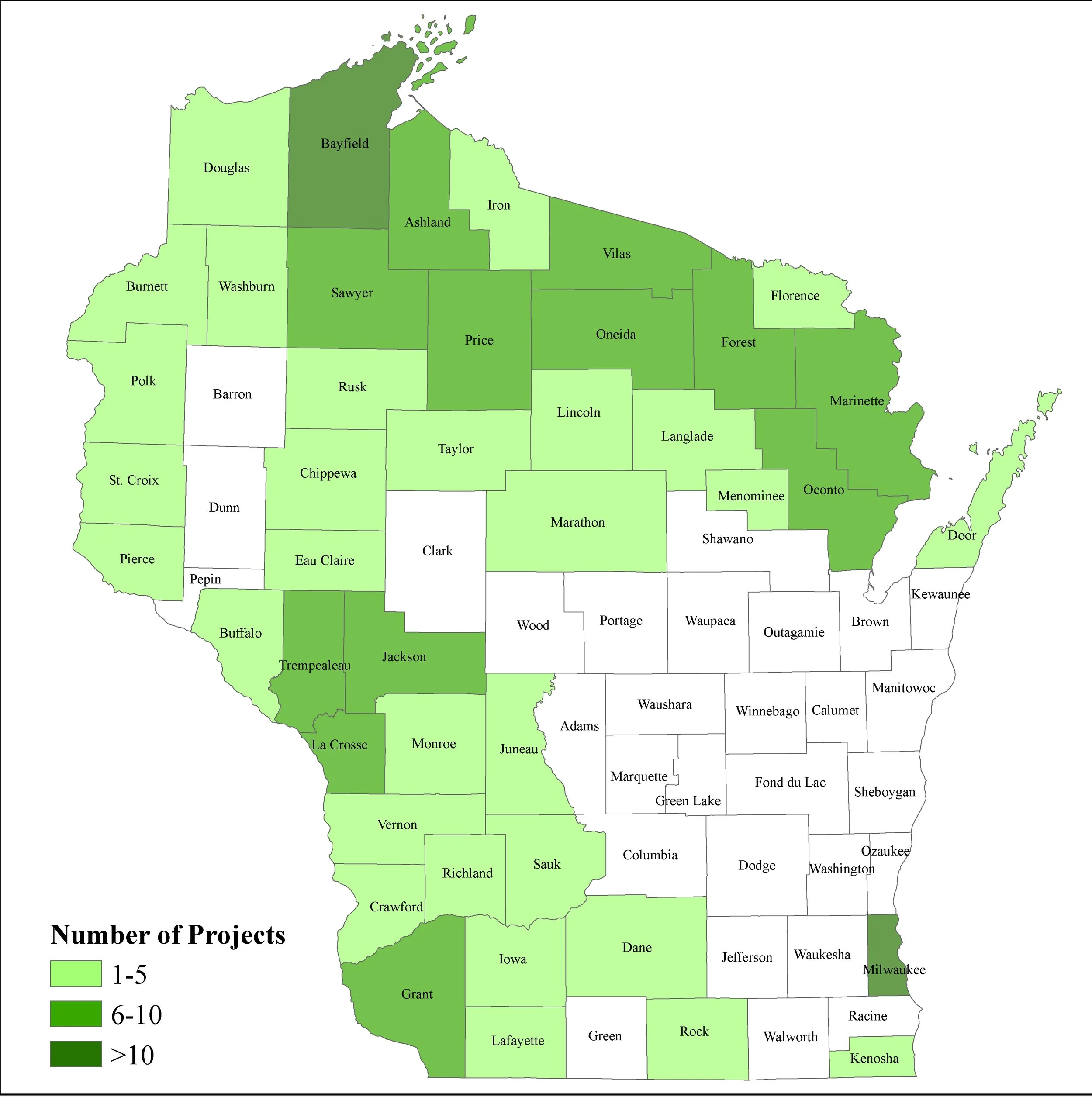

In response to the Great Depression which began in 1929, and as part of his New Deal agenda, President Franklin D. Roosevelt championed the formation of a civilian conservation workforce that would address both unemployment among America’s youth and environmental degradation that resulted from drought and decades of nominally regulated land and resource management practices. This program, which would later become the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), deployed enrollees to camps throughout the country. In Wisconsin there may have been as many as 182 camps distributed throughout 43 counties and administered primarily by three governmental agencies. As archaeological resources, CCC camps are poorly understood, though recent studies have begun to evaluate CCC camps vis à vis National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) eligibility criteria. This article presents an historic context for CCC camps, describes and summarizes the types of camps that operated in Wisconsin, and presents a documentation strategy and research questions that relate to NRHP eligibility.

Figure 2. Number of CCC camps per county. (Illustration prepared by Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc., based on information provided by CCC Legacy [www.ccclegacy.org] accessed February 2019).

A Synthesis of Wisconsin Maritime Archaeology

Victoria Kiefer, Tamara Thomsen, and Caitlin Zant

With over 1,000 miles of Lake Michigan and Lake Superior shoreline and hundreds of miles of navigable riverways, including the Mississippi, St. Croix, Wisconsin, and Fox Rivers, Wisconsin has depended on, and benefitted from, maritime transportation for millennia. The Wisconsin Historical Society’s Maritime Preservation and Archaeology Program has been exploring the State’s rich maritime history since 1988. Over the last 30 years staff archaeologists have dove into an array of archival records and documented a submerged fur-trade post, fish weirs, ancient watercraft, dugout canoes, docks and cribs, inundated mines, and nearly 200 historic shipwrecks located in the Great Lakes as well as inland lakes and waterways. While the program has investigated a diverse range of sites, its attention has been focused on the maritime historical resources of the Great Lakes due to preservation concerns, funding, and avocational and community interest. There are more than 700 reported losses of historic vessels in Wisconsin waters. Of these, roughly 190 have been located, half of which have been surveyed and analyzed by the Society’s maritime archaeologists. These examinations are the focus of this article.

Figure 5. Maritime archaeologist mapping artifacts on the Success shipwreck site in Lake Michigan (photo by Tamara Thomsen, Wisconsin Historical Society).